We the Parasites by A.V. Marraccini

WE THE PARASITES

A.V. Marraccini

Sublunary Editions, 2023

There was a fig tree in front of the old SPD warehouse in Berkeley where I used to work. A fig bush, really, until one of my coworkers pruned it into more of a tree. For a few years the figs had a soapy flavor I attributed to the formerly industrial character of the neighborhood, but then they started to sweeten because, I imagined, of the deepening roots.

Here’s a weird thing about some kinds of figs: there are male and female figs. The fig is an inverted flower, which needs to be pollinated to make the fig fruit that we eat. There are male and female fig wasps. The female fig wasp burrows into the male fig, called the caprifig, and the process, in turn, is called caprification, when she lays eggs and those eggs hatch. The hatchlings are blind, flightless males and young females. They have incestuous sex. The now pregnant female wasps, the one Aristotle and Theophrastus call psenes, burst out of the skin of the caprifig and go off to burrow anew into other figs. Both erroneously thought this was a kind of spontaneous wasp generation, but to be fair the actual mechanism is hard to discern such that the biology of it is still a topic now.

Figs and wasps are Marraccini’s first way into describing the triangulation that characterizes the role of the critic. Both fig trees and wasps are obeying their evolutionary imperative, but in the process of what Marraccini rightly names commensualism and mutualism. And beyond this, Marraccini, who tastes the figs and kisses them onward to us.

Readers also enter through this initial invocation of Aristotle and Theophrastus, whose erroneousness in this context Marraccini identifies and moves on from. We are not doing science—this is a natural history of a critic, and moreover one whose classical training and predilections (as a youth she kept the Fagles translation of Homer’s Iliad under her pillow) will provide a counterpoint to thinking the critic (thinking herself as critic) by considering parasites.

The tapeworm moves like a root in the darkness of the gut. We grope with our roots, searching for nourishment. But our roots are also a way of talking about our teachers and forbears:

I lied when I said I was “somehow” reading The Centaur. I’m reading it because one of the people who taught me, who formed me into a wasp instead of a bee or a wind, had just read it. He says it is about fathers and sons, about being both. I will never be either. I think about Chiron and Achilles, rather than Prometheus, to whom the novel refers.

This is lineage bent, slant, queered. How familiar the experience of not being what those who formed you expected but being the one who nonetheless arrived. The call wasn’t meant for you, but you received it and answered, as if hailed.

We the Parasites is, in part, an entry into Cixous’s School of Roots, the roots which are formed by pedagogy and desire, and the parasitical nature of desiring art. We the Parasites is a story of becoming, a pandemic diary, a narrative of queer love lost and, perhaps, regained.

Even before I received We the Parasites, having a feeling that it would be up my alley, I started following Marraccini on twitter, where I have a mostly spectral presence, learning in this way that she is a fellow at the Warburg Institute. I took this as a sign, being a devotee, albeit through secondhand kisses (to use Marraccini’s idiom) of Warburg’s recombinatory librarianship.

I read We the Parasites on the plane to Seattle from Bradley Airport in Connecticut, the closest to my home in Northampton, MA, having spent the morning talking to my friend Ruth. She was in my Creative Reading class, but we had never met in person. We got to talking about eels (whose mechanisms of reproduction are even more arcane than wasps) and books that purport to be about fish but are actually about scoundrels. I invoked Sebald’s shimmering sardines. Two hours later I am at 30,000 feet, swimming in Marraccini’s rose petals and porphyry.

What is the relationship of nature and metaphor and why can their union in writing so easily go awry? Another friend has been texting me about the superabundance of lackluster autofiction, and I think that natural metaphors are this way, too: terrible when mediocre but when it works, they are exquisite. Is it a matter of exegesis versus eisegesus? I don’t have a theory at the moment, just an admiration. I put Marraccini on the side of the angels, and I am with her from wasps and fig to tapeworm and fish louse.

Another friend texts me to say they are sorry they couldn’t do the Creative Reading class, but adds, “I just had a thought today that I wonder if animal tracks — reading them – was one of the earliest forms of reading. Following the imprints of different feet…” All I can think to say back is that maybe regarding animals is the origin of most aspects of human culture.

I find in Marraccini a fellow traveler, touched in youth by the same madness, flung from Florida to New Haven and finally to London. This triangulation, mediated by a middle place, is well-known to me from both literature (Azareen van der Vliet Oloomi’s Call Me Zebra, for instance) and from my own life, going from Texas to California to Massachusetts, an arc I have permanently inscribed in my bio because of its significance to me.

The non-place of night, with its foxes. The long pause of the pandemic.

Perhaps I felt even more invested because of how much Marraccini lingers on the feeling of her own belatedness, and on the parasitical nature of the critic—which I extend to writers like myself, early initiaties (and self-initiates) into lineages and libraries to the extent that, like Mrs. Who in Madeline L’Engle’s A Wrinkle in Time, when we open our mouths to speak, another voice comes out.

Marraccini grounds this in multiple ongoing images: first, the wasp, then the fish louse (which, I learn, literally becomes a surrogate tongue for the fish whose tongue it consumes). One of my favorite images is of the critic as an interceptor of kisses. She interposes herself to receive the artwork’s kiss and to kiss it onward to its viewer. Incidentally this puts me in the mind of Hannah Emerson’s The Kissing of Kissing, in which kissing is not merely a sign of affection but ontological state, epistemological instrument, hymn to the divine.

So what isn’t criticism? Criticism is not stealing art to hoard it out of sight, nor can it be a kiss pressed onto an artwork by tinted lips, although the plaint of the art kisser, “J’ai fait juste un bisou” (It was only a kiss) becomes a refrain throughout the book, as if to say, “One must not kiss the art, unless…” Marraccini orders the unless to resound, giving the kiss of the critic its frisson.

I hope I’m not leaning overmuch on Eros because Thanatos is here too. Marraccini takes us to Cixous’s School of the Dead, as we are all taken, both by life itself and by the (quite unevenly) universal experience of the pandemic. My reading of We the Parasites was colored by recent readings of books that might at first glance seem outside the borders of Marraccini’s critical, para-critical, and personal divagations. Marraccini’s anemia coexists with the hot-bloodedness (angry, at moments, but mostly ardent) of her prose and thought. The result is that I found myself thinking about Harrow from Tamysn Muir’s books. Marraccini works the art of Cy Twombly, Homer, wasps, in a cultural thaumaturgy reinforced by passages like this:

Let’s call this the Eurydic rite, the one where we refuse to come back up. We make home here on the flat path of the underworldly plain, our Necropolis, our school of velveteen rays. We live as much in death than in living now. And when a god comes to us in a traveler’s hood and winks we know exactly when to play it dumb. Tear all the cloth. Dance in your winding clothes. Put down roots, grow with the hungry hybridity of the graft. Feed with your needle mouth on the rich porphyry veins of the world.

And:

When I write about Rilke I re-animate him, drag up his shade for a chat. Or maybe I send myself down, down there, and decide to stay or at least get a passport. The Necropolis is my city too now, one in which the white roots of the daytime world are all coming up roses, that crush or bloom invariably their own craterous timelines, in which the tentative is everything, the animate risk of the cell.

Likewise, Marraccini describes herself as a literal interloper. The American woman (bar bar) who penetrates the patriarchal enclaves of a Cambridge club, surprising the classically educated peerage by reading Theocritus. I can’t help but think about RF Kuang’s Babel, generically far but queerly kindred to We the Parasites. A great and terrible lineage, stolen from thieves.

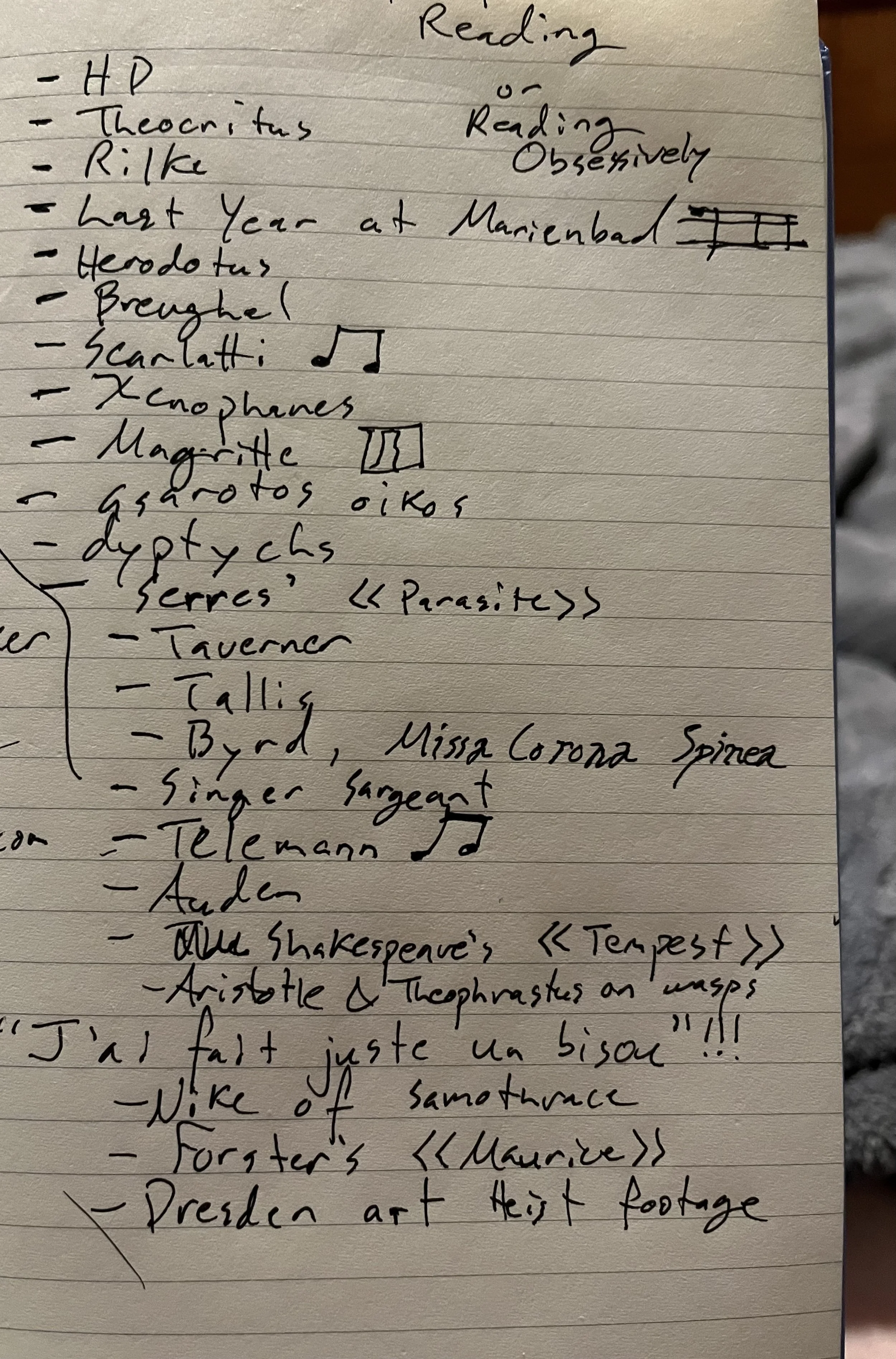

And of course Genet is here, patron saint of thieves and parasites, along with many others. We the Parasites performs one of my favorite functions of a book, that it could be a curriculum. Not being an instance of academic writing or formal art criticism, it doesn’t have the same textual apparatuses, but I started sketching the bibliography. Here’s part of it:

I am influenced in this way by my year-long reading group of the HD Book, whose original vision was to read both the text itself and then to engage with each of its references. I think doing that with We the Parasites would be immensely rewarding, but I’m still figuring out who else wants to read so devotionally and obsessively, and how to invite them in.